The “Pennsylvania Dutch” were German-speaking immigrants who came to the Americas in the 17th and 18th centuries, following the aftermath of the Thirty Years War in central Europe. Most of them came from what is now known as Germany – but the during that time period, it was known as the Holy Roman Empire, as Germany was not founded until 1871.

The Pennsylvania dutch mainly migrated to the state of Pennsylvania, but many others resided along the upper East coast of the U.S., along with some in Eastern Canada. The word “Dutch” is derived from the word “Deutch,” translating to “German” in the English language. Pennsylvania Dutch has no actual relation to Dutch people.

The term can sound misleading for these reasons, so over time it has also been known as: Pennsylvania German or German American. It can also be shortened to “PA Dutch” or “PA German.”

The PA Dutch (German Americans) have a unique culture that is completely distinct from modern-day Germany. While the area that they migrated from continued to evolve on its own, the PA Dutch who separated themselves onto a new continent also evolved in their own way. Taking Medieval and Renaissance traditions of western Europe, they would become influenced by the Colonial era, as well as Native Americans, plus the other ethnic groups who migrated.

The Pennsylvania Dutch language

Just like every other ethnic group, the English sought to anglicize the PA Dutch. This included forcing them to speak English. The PA Dutch were extremely stubborn about holding onto their culture, tradition, and identity — more so than almost any other ethnic group coming to the Americas. They were one of the last few groups to stop speaking their own language — clinging onto German dialect for dear life.

The issue was that German was no longer being formally taught in schools, the way it was in their homeland. And no one else was speaking German outside of their families and communities. Kids were learning German from their parents, very informally, with strong English influence from the outside world. Because of these factors, their German language transformed into what is called the Pennsylvania Dutch language.

The Pennsylvania Dutch held onto their language longer than any other European immigrant group. (Spanish is a prevalent language today in America, but people have been speaking Spanish in this country long before anyone ever spoke English. Unlike Spanish, Pennsylvania Dutch is not indigenous to this area.) While other immigrants lost their language within 1-2 generations, the Pennsylvania Dutch held onto their language for 10+ generations — and is still spoken today in Amish communities.

From the late 1600s, Pennsylvania Dutch was widely spoken within the community until WWI and WWII, sometime between the 1910s and 1940s. The World Wars lead to massive anti-German propaganda and American pride, putting much greater pressure on the Pennsylvania Dutch to completely convert to English.

This statement about the Pennsylvania Dutch language reveals so much about their culture and attitudes. It shows great determination, stubbornness, and perseverance of these people. It tells us that they felt a passionate connection to their ancestors, traditions, and roots.

Plain vs. Fancy

The Pennsylvania Dutch split into two groups:

- Plain Dutch: The Amish and Mennonites who cut themselves from the outside world in order to fully preserve their ways. They believed in abstaining from worldly matters and living a simple life.

- Fancy Dutch: The Lutherans, Reformed, Catholic, and those who chose to integrate into society.

Many people who hear the term “Pennsylvania Dutch” (or sometimes even just the state of Pennsylvania), think of Plain Dutch, or the Amish people who live strict and isolated lives. But most descendants of the Pennsylvania Dutch come from the Fancy Dutch, who have fully blended into the modern world.

You could call this divide conservative verses progressive. The Fancy Dutch still fought hard to maintain their language and cultural ways, but of course, this is impossible to completely preserve unless you are removed from external forces, like the Plain Dutch.

Religion & spirituality

Religion was at the heart of the PA Dutch people. Their religion was Christianity, branches including Anabaptist (Plain Dutch), Lutheran, Reformist, and Catholic (Fancy Dutch.)

Church was a huge part of their community. Services were another way in which they kept their Pennsylvania Dutch language alive, with hymns and sermons spoken in their dialect. Church was another factor that strengthened their community, as small towns gathered together each Sunday.

Folk religion was not as widely, or openly, practiced by the PA Dutch in the same way as conventional Christianity. While Folk religion is based on Christian beliefs, it incorporates superstition and supernatural in a way that the religious institutions did not. But we do have evidence of the Pennsylvania Dutch using magic and spells.

In 1820, John George Hohman published a book titled “Der Lange Verborgene Freund” which translates to “The Long-Lost Friend.” And in 1856, it was translated to English.

A collection of herbal formulas and magical prayers, The Long-Lost Friend draws from the traditional folk magic of Pennsylvania Dutch customs and pow-wow healers. – The Long-Lost Friend: A 19th Century American Grimoire

The folk practice is called “Braucherei,” also known as “pow-wow.” It typically combines herbalism with prayer. It’s used for anything from sickness, to crop failure, to spiritual protection from witches and black magic. A Braucher is someone who is trained and educated on this subject, and can pass their knowledge to others.

Folk magic is something that spans across all cultures and ethnicities — but in very different forms. Example include: Santeria (West African), Vodoo (Haitian), Stregoneria (Italian), Tantra (Indian), and Shamanism (Native American.) And in Pennsylvania Dutch, it’s Braucherei or Pow-wow.

Folk art: Fraktur and Hex signs

Another defining trait of the PA Dutch is their unique style of art. It’s vibrant and bold, including all colors of the rainbow, especially orange and red tones. Patterns are usually symmetrical. Artwork tends to include birds, suns, stars, hearts, and flowers.

Fraktur is style of script that was often used on documents such as birth certificates and religious texts. Legal documents also included elaborate artwork.

Hex signs are an absolute staple of the Pennsylvania Dutch. They are circular designs, varying from simple to complex. Hex signs are usually placed on barns, but can be hung up anywhere around the home. They are said to bring good luck and protection.

The word “hex” comes from the German word “hexe,” which translates to “witch.” It’s likely that hex signs were more than purely decorative — that they were intentionally used to bring spiritual protection. However, some historians argue against that claim. It’s possible that hex signs were decorative for some, but more spiritual for others.

There is no definitive meaning for each symbol used on a hex sign (that we know of!) But across all hex signs, you do see repeating symbols.

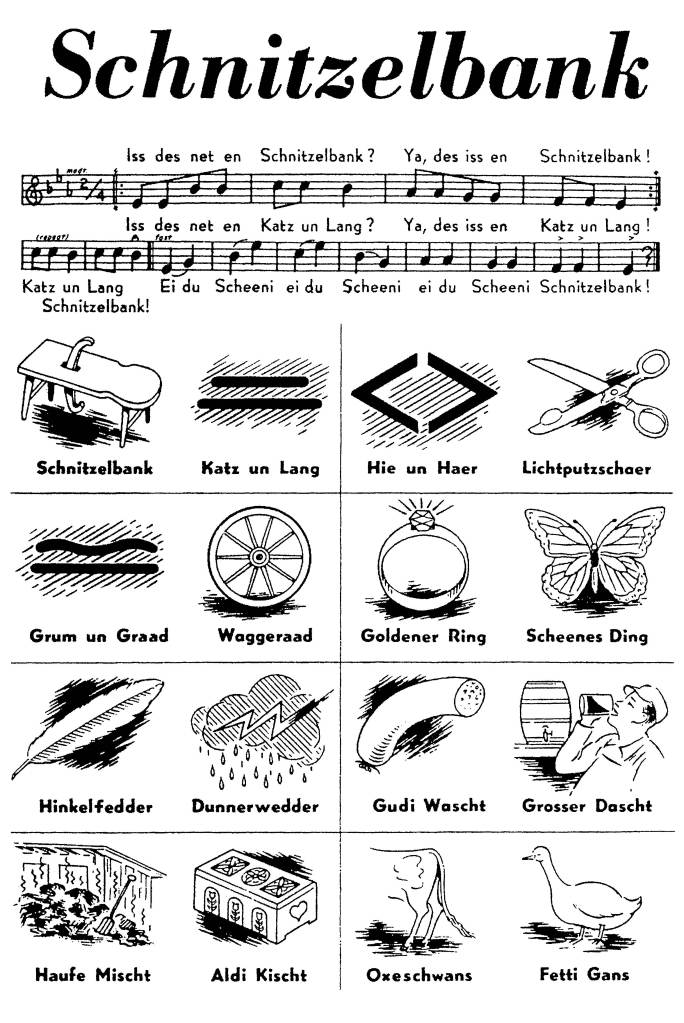

“The Schnitzelbank Song”

“The Schnitzelbank Song” is a tradition in many German American families — and predates immigration from Europe. It’s a nursery rhyme for children which became a piece of entertainment, humor, and nostalgia for adults.

The leader stands in front of a poster and uses a stick to point to each item. While the leader moves over each item, the crowd sings back. It sort of goes in the style of “12 Days of Christmas,” in which a new item is added to each verse.

Leader: Ist das nicht ein Schnitzelbank?

Crowd: Ja, das ist ein Schnitzelbank.Leader: Is that not a woodcarving bench?

Crowd: Yes, that is a woodcarving bench.

The entire song is sung in the language of Pennsylvania Dutch. It’s meant to be humorous, goofy, and silly. It’s a tradition that many German American families have brought into the 21st century.

Holidays

The Pennsylvania Dutch have always loved holidays, typically based on religious tradition. Fastnacht Day is their version of Shrove Tuesday (or “fat Tuesday”), which falls on the day before lent. The intention is to bulk up on delicious food before the period of fasting and sacrifice.

Fastnachts are doughnuts made from fried potato dough. In typical tradition, they are baked on Fastnacht day in large batches. Many people currently celebrate this holiday, from families to congregations to bakeries!

Groundhog Day was invented by the Pennsylvania Dutch and has become a national holiday in the United States and Canada. It comes from the PA Dutch superstition that on February 2nd, if a groundhog sees its shadow, there will be six more weeks of winter. If it does not see its shadow, it means that spring will come early.

The holiday is rooted in superstitious belief, which proves that the PA Dutch were indeed influenced by folk magic practices. In modern times, a formal ceremony is held in western Pennsylvania in which it is publicly declared if the groundhog (Punxsutawney Phil) has seen his shadow or not. Tracing back to western Europe, the holiday was originally known as “Badger Day” in which the groundhog was formally a badger.

Groundhog Day aligns with Candlemas, which does have Christian roots. It marks the presentation of infant Jesus at the Temple in Jerusalem. But if you go back even further, you’ll find Pagan roots, with February 2nd marking the halfway point between winter solstice and spring equinox (known as Imbolc.)

The Pennsylvania Dutch also celebrated Easter. In fact, the Easter bunny comes from Germanic folklore. The Easter bunny judges children based on good or bad behavior. It carries a basket with eggs, candies, and toys — handing them out to those who are good. In modern times, the Easter bunny has become a core part of the holiday across all people and backgrounds.

Germanic roots are responsible for most Christmas traditions, including the Christmas tree, the advent calendar, and Santa Claus (although Santa Claus comes from a compilation of several myths and backgrounds.) One tradition most specific to the PA Dutch is The Belsnickel. It traces specifically back to the Rhineland-Palatinate area of southwestern Germany.

The Belsnickel dresses in fur and has a disheveled appearance. He travels alone, visiting houses a couple of weeks before Christmas, to determine good or bad behavior. He interrogates children and keeps them in check, warning them that they won’t get any presents if they aren’t on their best behavior. And he’s not afraid to use his whip.

Food and drink

The Pennsylvania Dutch have many different foods.

- Scrapple and sausages

- Shoofly pie

- Apple butter

- Pretzel soup

- Fastnachts

- Apple dumplings

- Egg noodles

- Beer and cider

- Cream liquor

- Dandelion wine

- Birch beer / root beer

Putting it all together, you can learn a lot about the Pennsylvania Dutch by looking at their history. They were determined and persistent people who stubbornly held onto their roots. Many of them, the “Fancy Dutch,” spread into society and dispersed overtime. Some of them continue to hold onto traditions such as Fastnacht Day and The Belsnickel, while other traditions such as Groundhog Day and the Easter bunny are commonly recognized by all.

The Pennsylvania Dutch had their own representation of folk magic and supernatural beliefs through what’s known as Braucherei, or Pow-wow. Unlike Santeria or Voodoo, this folk practice is based on Christian beliefs. Christianity was the center of the Pennsylvania Dutch people.

The bold and vibrant artwork of the PA Dutch reflects their upbeat, positive, and bright attitudes. It shows happy spirits with animated energy. The tradition of “The Schnitzelbank Song” conveys humor, goofiness, and lightheartedness. And their holiday traditions reveal how much folklore is a part of their lives.

Overall, I see people who put value into passing down myths, traditions, and practices. Their ancestors were not only stubborn and willful, they were funny and high-spirited. And if you have this in your family tree, perhaps you can feel this energy in yourself.

Leave a comment